By Lila McRae-Palmer

Lila Needs to ‘Estop’ Focussing on Memorisation and Focus on Application.

A Hypothetical Case

Facts: Lila is a first-year JD student. She has never learned how to study for subjects that required application rather than memorisation. Lila could tell you what year pottery was invented in Ancient Egypt but in Mathematical Methods, Lila struggled to apply the rules for solving a function if it was (-3/2) rather than (-2/3) because Lila had only ever seen (-2/3) and therefore every method of solving the function went out the window and this new, scary problem meant she could no longer solve it. Lila has realised that she is facing the same problem with her law subjects: if Jenny had given 20k to Bob Parker for a house that Bob Parker refused to give her and was awarded 20k in an equitable remedy and the new hypothetical on the exam meant Lisa gave Bill 30k, Lila no longer knew what a ‘reasonable’ remedy would be because she had only ever dealt with 20k not 30k.

Question: Advise Lila on what she should do to better tackle law subjects that require adaptable application techniques rather than sheer memorisation.

Issue:

Lila has only ever learned how to rote learn and memorise facts. Lila must now learn how to apply rules that were learned to a new set of facts.

Rule: e.g. ƒ(issue) = 3(rule + application)² + conclusion

The key to doing well in law subjects is learning legal rules and citing authority for these rules. It is not to memorise how much money Jenny paid to Bob in a past hypothetical, because the new hypothetical facts must sub into the place of the function (rules) – the function does not change, meaning the framework (or checklist) does not change. You must apply the rules for the given topic and the content (new facts) will only indicate to you what you must discuss: what rules to apply.

Application

To apply this rule, Lila must learn how to focus on solving the problem through applying a rule, not drawing on Red Herrings from a hypothetical case.

Conclusion

I would advise Lila to stop trying to memorise 600 pages of a case with all its tiny details and 2000 pages of a textbook and instead focus on the key questions/discussion points of each class and what the cases/readings are trying to tell you. I would remind Lila that she is not the key litigator in this 1852 case so it is not necessary to remember that Johnny worked at a bank in England over his Summer break on a 2018 practice exam, but it is necessary to remember that this fact should trigger the application of a rule that will frame the analysis of the problem and guide her to the solution.

Commentary

Starting my Juris Doctor triggered an epiphany for me: I had never learned how to learn.

My experience in school was that we had multiple sessions about how to study, like using ‘The Pomodoro Technique’ where you study 20 mins on, 10 mins off.[1] We were taught to use flash cards and then attempt as many practice exams as we could. I knew many of my peers who somehow memorised full-length draft essays for the English exam to apply if given that topic.

[1] Francesco Cirillo, ‘The Pomodoro Technique (The Pomodoro)’ [2006] Creative Commons.

We would write the notes, memorise the notes. Over and over.

I realised I had only ever been taught about time allocation, rather than what it was I was actually trying to achieve by allocating such time. I would read the textbooks and memorise parts of it expecting it to magically make some connection in my brain as to how to actually solve a problem or respond to a prompt.

I have relied on my memory for as long as I could remember as my main form of ‘study.’ Flashcards and memorising content by writing it out over and over meant I developed a strong visual memory of which I could recall multiple paragraphs from a word trigger.

However, this only gets you so far, and more so helps for subjects that rely on recalling facts i.e., History – key dates, key people; Biology – recalling names of cells etc.

The subject I struggled the most with in school was Mathematical Methods. The method of study I had used throughout my education was always just flashcard memorisation or physically writing sentences that would help me memorise content we had been taught. I had never learned how to learn a formula and apply it to a new set of facts of which had not been covered. I realised that this is what my law subjects were expecting of me – learning a rule, applying it to new facts.

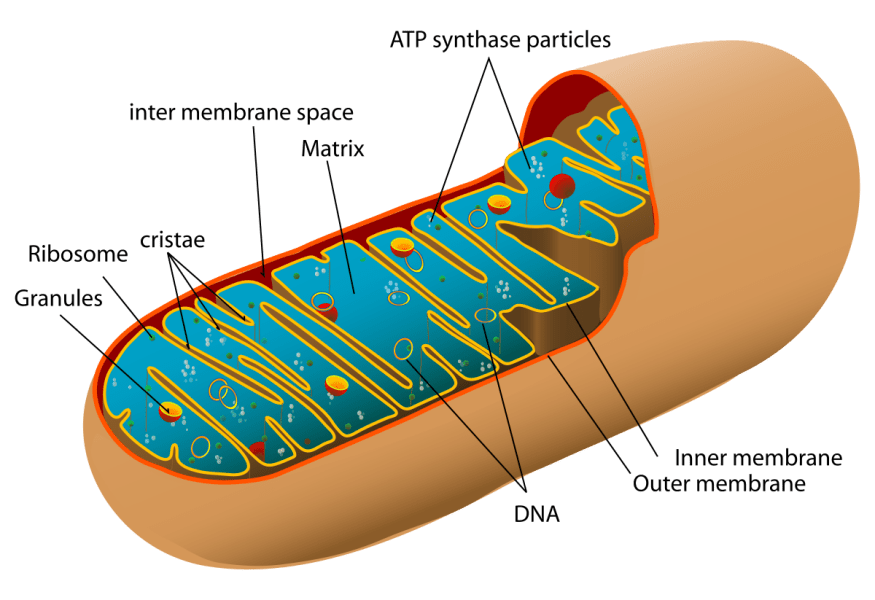

could tell you verbatim what the mitochondria does, but I could not have told you how to solve a function if they put a negative fraction in there that happened to have a 3 as the denominator instead of a 2.

In order to know the rule, you must understand when to apply it. Not all rules will be applied to all problems, and the exact numerical problems you had seen in a practice exam for Methods, or in problems in class, were not going to be on the test in front of you. You are presented with new combinations of numbers (facts) in the place of the ones you had studied, and you are expected to apply formulas and pathways of analysis in order to solve the problem.

I realised the part I was focussing on was the specific facts (numbers/symbols) involved in the problems I was practising, not the pathway for solving it. This led me to some unfortunate grades, but what was worse, it had led to me not learning the required content properly.

When I first started writing hypotheticals in the JD, I found it painfully hard to know where to look to analyse the facts and knowing what rule to apply and when; with so much information comes the expectation that you will reduce down to what is necessary to discuss. Put simply, for Maths: if your problem is 1+1=? you should not try to divide the answer you have arrived at because that is not what you are being asked to do: you are being asked to add it. Additionally, learning to add 7+7 should not change the way you add 1+1 because it is the same method of solving the problem.

Having this realisation was incredibly necessary for my brain to be able to understand why I was struggling to analyse a hypothetical succinctly. A new set of facts did not actually mean I was being expected to know something knew, it meant applying rules I had already learnt with a few different words in there (like the different numbers for maths).

I acknowledge that perhaps this may be common sense for many, but for some reason, relying on my memory of things I had been taught in class, rather than applying a method for solving a problem and adapting the method to new questions, was just the way I had learnt to learn; or more so, to study. I also think it is important to discuss the differences between what we constitute as learning and what we constitute as studying, because they are relatively vastly different things but often treated very similarly in education.

Closing testimony: memorising context is what you should focus on, not memorising variable content/facts, because you are expected to apply the rule (context) for a problem you have previously seen, not apply the facts (variable content/facts) you have previously seen.

Leave a comment