By David Minahan

Celebrating intersectional identity at MLS.

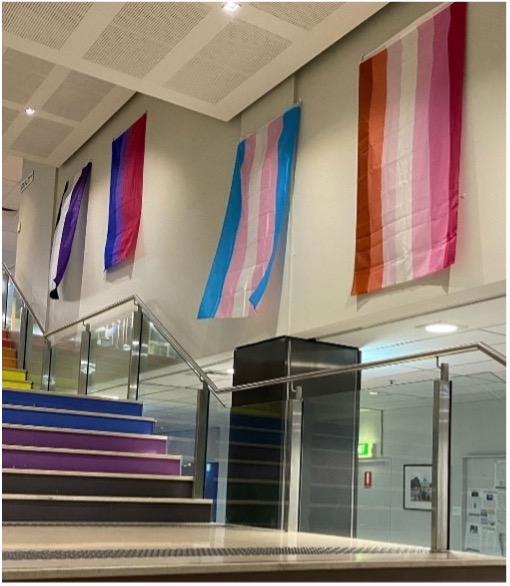

The staircase leading to the Melbourne Law School (MLS) library — known as Equality Way — is lined with pride flags that celebrate the diverse identities within the LGBTQIA+ community. Among them is the Progress Pride Flag, which incorporates black and brown stripes to represent marginalised communities of colour.[1]This flag is a meaningful step toward intersectional representation. However, one important intersectional identity appears to be missing from the staircase: LGBTQIA+ people with disabilities (LGBTPwD).

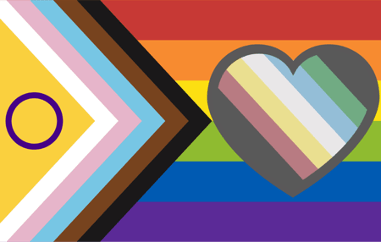

In 2024, the Disability Inclusive Pride Flag was unveiled at London Pride festival and brings visibility to this very intersection.[2] The new flag incorporates the LGBTQIA+ Progress Flag with the Disability Pride Flat.[3] (You can learn more about the flag here)

I write this article to advocate for this flag to be displayed on the Equality Way staircase. I do not believe that the flag is commercially available yet, however, it may be possible for students to make such a flag. I hope that LGBTPwD students at MLS can lead this initiative, potentially with the backing of MULSS and/or PILN. I am not a member of the LGBTQIA+ community and do not seek to be involved in the flag’s production. I merely wish to raise awareness for the need for greater visibility and acceptance of this intersectional identity at MLS.

Image description: Image of the Disability Inclusive Pride Flag. On the left, a chevron points right, with stripes in black and brown (for people of colour), light blue, pink, and white (for the transgender community), and yellow with a purple circle (for the intersex community). Behind the chevron is the rainbow flag with red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple stripes. On the right, a heart with a light black outline contains diagonal stripes in light black, green, light blue, white, yellow, red, and light black. These colours represent the Disability Pride Flag.

Why this intersectional identity matters.

Many LGBTPwD feel compelled to conceal their LGBTQIA+ and/or disability identities because of the stigma associated with them.[4] As a result, many people may overlook or underestimate the presence of this group. However, LGBTPwD are likely more common than many realise. In a US-based survey, one in three (36%) LGBTQ+ adults reported having a disability, compared to one in four (24%) non-LGBTQ+ adults[5] Additionally, over half (52%) of transgender adults reported having a disability compared to more than a third (35%) of cisgender LGBTQ+ adults.[6] These figures are probably higher because many LGBTQIA+ individuals may have undiagnosed disabilities.

Autistic individuals deserve particular attention when discussing this overlap. Research shows that Autistic people are more likely to be LGBTQIA+ than the rest of the population:[7]

- Autistic individuals are roughly seven times more likely to not identify as cis-gender than neurotypical people.[8]

- Nearly 70% of the Autistic community identify as non-heterosexual.[9]

Displaying the flag can help draw attention to the often-overlooked challenges facing LGBTPwD. Some of these challenges include:

- Intersectional oppression: LGBTPwD are adversely affected by multiple levels of oppression and stigmatisation, such as ableist, heteronormative, and cis-normative public perceptions.[10] For instance, lesbian women with a disability may face prejudice arising from their sexuality as well as their disability.[11]

- Negative experiences: LGBTPwD experience higher levels of discrimination and harassment than their non-disabled LGBTQIA+ peers.[12]They also have poorer experiences and/or outcomes in respect to many aspects of life, including education, employment, and relationships.[13]

- Double exclusion: LGBTPwD often feel isolated due to a sense of being unable to fully belong in either community.[14] Many frequently experience rejection from both communities: from LGBTQIA+ spaces for their disability or their disability’s traits, and from disability spaces for their sexuality or gender identity.[15]

- Invalidation of identity: Many professionals and family members often dismiss LGBTQIA+ Autistic peoples’ gender and sexual identities.[16]They mistakenly assume their identities are a result of confusion stemming from their autism.[17]As a result, many LGBTQIA+ Autistic individuals frequently have their identities discredited and their perspectives invalidated.[18]

- Stereotyping about autism: Some in the LGBTQIA+ community hold stereotyped views of autism and may not be aware of the diversity within the autism spectrum.[19]

These challenges illustrate that there is still some progress to be made in changing attitudes towards LGBTPwD and promoting their acceptance within both their respective communities and broader society.[20] Increasing acceptance within both the disability and LGBTQIA+ communities is especially important because these communities offer LGBTPwD a sense of belonging and social support.[21] This in turn plays a significant role in fostering their resilience and self-acceptance.[22]

I believe that displaying the Disability Inclusive Pride Flag at MLS could meaningfully contribute to this goal. It would promote awareness and spark important conversations around the unique challenges faced by LGBTPwD, such as those described above. In doing so, the flag could encourage greater inclusion within both communities at the law school. Its presence may also serve to validate and affirm the identities and lived experiences of LGBTPwD. Ultimately, the flag may be a powerful step toward helping these students feel seen, supported, and truly valued during their time at MLS.

Let’s make Equality Way live up to its name.

[1] Ariane Resnick, ‘What Do the Colors of the New Pride Flag Mean?,’ Verywell Mind (Blogpost, 30 September 2024) <https://www.verywellmind.com/what-the-colors-of-the-new-pride-flag-mean-5189173>.

[2] Annie Heven, ‘Disability Inclusive Pride Flag unveiled at London Pride,’ EvenBreak (Blogpost, 2 July 2024) <https://blog.evenbreak.co.uk/2024/07/02/new-disability-inclusive-pride-flag-unveiled-at-london-pride/>.

[3] I have asked faculty to display the Disability Pride flag in the law building.

[4] Theofilos Kempapidis et al, ‘Queer and Disabled: Exploring the Experiences of People Who Identify as LGBT and Live with Disabilities’ (2024) 4(1) Disabilities 41, 46 (‘Queer and Disabled’).

[5] Human Rights Campaign Foundation, ‘Understanding Disability in the LGBTQ+ Community’, Human Rights Campaign (Web Page, 8 December 2022) <https://www.hrc.org/resources/understanding-disabled-lgbtq-people>; See, Karen Fredriksen-Goldsen, Hyun-Jun Kim and Susan Barkan, ‘Disability among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: disparities in prevalence and risk’ (2012) 102(1) American Journal of Public Health 16, 18.

[6] Human Rights Campaign Foundation (5).

[7] There is no official scientific explanation for this overlap as far as I am aware. This is because there is probably no scientific explanation on what autism is exactly.

[8] John Strang, ‘Increased gender variance in autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder’ (2014) 43(8) Archives of Sexual Behavior 1525, 1529.

[9] R George and M.A. Stokes, ‘Sexual Orientation in Autism Spectrum Disorder,’ (2018) 11(1) Autism Research 133, 135.

[10]Kempapidis et al, ‘Queer and Disabled’ (n 4), 43.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid 59.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ashleigh Hillier et al, ‘LGBTQ+ and autism spectrum disorder: Experiences and challenges’ (2019) 21(1) International Journal of Transgender Health 98, 106.

[15] Ibid; Kempapidis et al, ‘Queer and Disabled’ (n 4), 43-44.

[16] Hillier et al (n 15) 104.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid 103; Kempapidis et al, ‘Queer and Disabled’ (n 4), 59.

[20] Kempapidis et al, ‘Queer and Disabled’ (n 4), 59.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

Leave a comment